I ran across this quote yesterday:

“Whatever became of the moment when one first knew about death? There must have been one, a moment, in childhood, when it first occurred to you that you don’t go on forever. It must have been shattering, stamped into one’s memory. And yet I can’t remember it. (…) Before we know the word for it, before we know that there are words, out we come, bloodied and squalling…with the knowledge that for all the points of the compass, there’s only one direction and time is its only measure.” – Tom Stoppard #TomStoppard

I knew about death a long time ago. The Catholic religion makes sure of that. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Ashes on my forehead to remind me where I was going. The abundance of dead Jesuses on crucifixes everywhere in my life. Viewing dead relatives in caskets. It was never a shock. The Catholic religion has often been called the religion of death. We spend our whole lives – as Christians – preparing for an “afterlife”.

My maternal grandmother died when I was two. I don’t remember that, or her. But, I had a yellow stuffed bear that I was told she had given me. I always carried it with me. It was in my bed at night. I took it with me on car trips. I still had it when I left home at 18. It was special to me. One day I threw it away. I wanted no more reminders of my childhood. I was an adult, and looking forward.

But that came much later. As an infant, I had pneumonia – ended up in an oxygen tent in a hospital. Two years later, after being taken to a Thanksgiving Day parade in downtown Baltimore, I developed pneumonia again. No hospital that time. Doctors made house calls. I was given medication. Years later, I had another bout. I mostly remember how hard it was to breathe, and the green slime I would cough up from my lungs. My parents got a steamer for me. It was a light green glass thing, shaped like a cake – cylindrical, about six inches high. Filled with water, it was plugged in to generate a column of steam towards me. I was cautioned not to touch it. One time, as I was sleepily turning over, my hand fell on the steamer. I got a bad second-degree burn. I was so careful after that. Eventually, they put it away. I seemed to be better. Then I developed asthma and had breathing problems for years. Close to death, but never quite there.

In second grade my parents told me that one of my classmates had died – he had choked on a glass of water. I couldn’t imagine such a thing before that. Perhaps that was the moment I realized death could come at any time, for anyone, regardless of age. Then my cousin Lucky died of cancer – leukemia, I think. Perhaps a name like Lucky was tempting fate. My uncle still grieves, and my aunt died years ago.

I had my own brushes with death many times. I fell into the freshly dug cellar of a new house once. Me, my brother John, and our friend Eddie Knight were grabbing the largest stones we could find and dropping them down the hole in the floor where the steps would go. My idea. There was nothing down there then, just a pool of muddy water from a recent rain. What fun it was to watch the big splashes! We dropped our rocks and then went searching for more. At one point, Eddie pushed a large rock up onto the floor that was all that existed of the house then. It was about four feet above ground, so we had to climb up. We were about six years old at the time. I wanted to drop that big rock Eddie had, so while he was climbing up, I grabbed it and dropped it in.

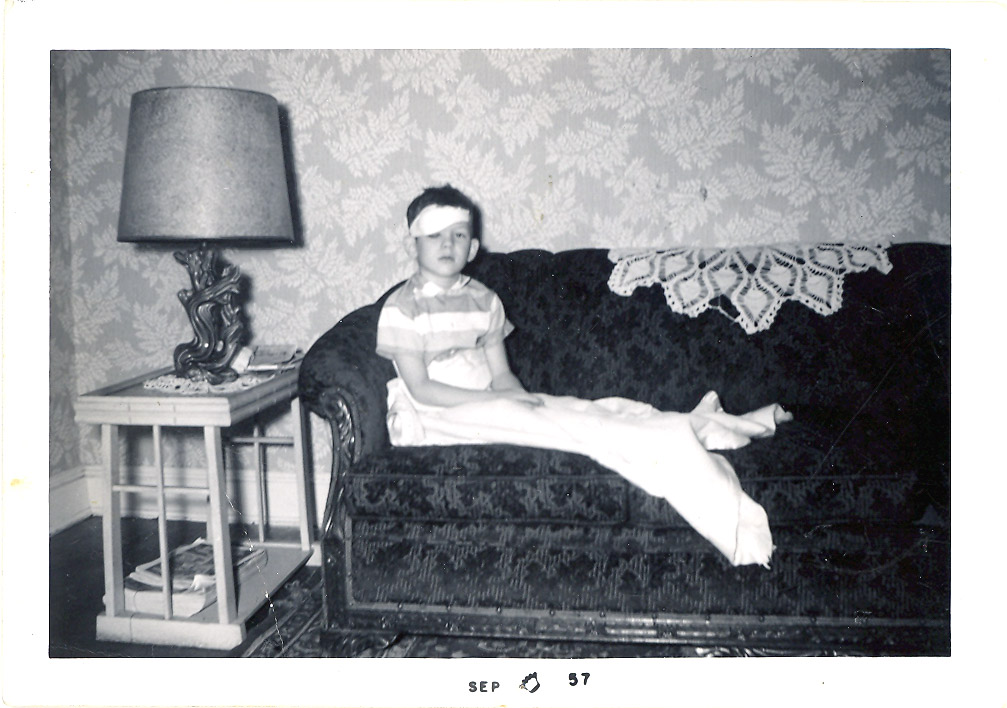

The next thing I saw was Eddie running towards me, then nothing. I remembered being carried across the field behind our house – a fair distance from where we’d been. I opened my eyes briefly – my face was wet, but I passed out again. My mother said my face was covered with blood when they carried me in the back door. I had hit my head on something down there – probably the very rock I’d dropped. My brother found a way down somehow and found me unconscious in the pool of water, face down. He saved my life. Eddie had gone for his parents, who had carried me.

Just a bit over two years later, I developed appendicitis after the first day of 4th grade. I didn’t know what it was at the time, and neither did my mom. She put me to bed with aspirin for the pain, but it didn’t help. For a week, I was in intense pain, and getting weaker. She had no idea what was wrong with me. She called a doctor who said to bring me to the hospital. There was no way my parents could have afforded to call an ambulance – they found out what that cost when I’d fallen into the cellar – it had cut me above my right eye. With all that blood and my eye so close to it, they had to do it. My father now had the car at work, quite some distance away. This time, my mother borrowed a car from a neighbor and drove me to the emergency room. She parked on the street parallel to the hospital’s main entrance. There was still a wide sidewalk to negotiate. I couldn’t really walk. My left arm was around my mother’s neck, supporting me. I was too big to carry. She dragged me along until we got in. I can only remember snatches after that.

My stomach was x-rayed, and blood was drawn. The x-ray did not show anything. Appendicitis was suspected, but the appendix didn’t show in the x-ray. My blood, however, was full of poison. Sepsis. At the time I heard peritonitis – an inflammation of the stomach lining. I had to be rushed to an operating table for exploratory surgery. My appendix had ruptured. Later, they told my mom I’d had less than 24 hours to live. Appendix removed, I had a month-long stay in the hospital to drain the infection, during which time I turned eight years old. I was given penicillin every four hours. The incision was huge because of the exploratory surgery. There were a lot of stitches, and six tubes sewn along the incision to drain the poisons. I still have the scars.

Ah, death! Why were you always stalking me? Without penicillin, I’d have died quickly.

I continued to be lucky through high school. I only broke my arm falling from a tree once. It was not life-threatening.

After high school, I operated an X-ray machine used for physics research on silicon & germanium crystals at Johns Hopkins University – America’s first research university, located in Baltimore, Maryland. Baltimore was home to the Orioles baseball team, the Colts football team, and blue crabs from the Chesapeake Bay. The Colts skipped town one night to play for Indianapolis. After a few years working at the University, and taking the free classes employees were entitled to, I stopped working full-time to attend UMBC, the University of Maryland in Baltimore County. Oddly, the City of Baltimore is not in Baltimore County – it is its own independent entity.

Anyway, I left UMBC after two years. I learned a lot, but my grades suffered from all the breaks I took to protest the war in Vietnam, and the time I spent volunteering at the People’s Free Medical Clinic, an organization providing free medical care for the neighborhood I Iived in. I had also spent time taking classes offered by the Black Panther Party, who saw themselves as creating a revolution. They had a breakfast program for inner-city kids, and were primarily interested in self-defense and education. Inner-city cops were tough on black folk, and often unapologetically broke doors down on random houses while looking for people. The Baltimore City jail was vastly overcrowded, mostly with young black men. [see: https://wp.nyu.edu/gallatin-bpparchive2021/east-coast-chapters/baltimore-md/ ]

Additionally, I hung out with the Berrigan Brothers, two Jesuit priests who had dragged Selective Service (Draft Board) files out and saturated them with blood (pig’s blood). Then, after they got out of jail, they created homemade napalm to burn the draft files, as a symbolic gesture in memory of the innocents, like farmers and young children, indiscriminately burned with napalm in Vietnam. Most people ended up opposing that horrible war, which I opposed as much as the Berrigans did, inspired by their actions. When the war was finally over, the North Vietnamese re-unified their country, which the French had colonized, leading to war. The Viet Minh eventually defeated the French, but the country was divided into two by the Geneva Accords that both sides had agreed to in 1954. The fighting to remove the French continued, however, and the French dragged the United States into their fight, then abandoned the fight, leaving the USA to clean up their colonial mess.

And, I was still plagued by bad luck or devilry or something. I lived in downtown Baltimore at the time and rode my bicycle back and forth to the UMBC campus, a twenty-mile round-trip every day. One morning, I was racing down a steep hill on a busy street. I was hot riding in that Baltimore humidity, so I put my feet to the metal (pedals) and enjoyed the wind caressing me. Suddenly, to my left, a car appeared. It had been going in the opposite direction, but was going to turn left into a freight yard driveway to my right. I was in the right lane of two southbound lanes, and cars in the lane to my left had stopped to allow the car to cross. Traffic blocked my view of that, so I was as surprised as the driver when we collided. I went sailing up and forward a ways, due to my speed, which was fortunate, since the huge white Continental crushed my bicycle under its tires as it proceeded across the lane I’d been in. I had time to think: 1. that I’d surely die in that traffic, and 2. that I was going to be late for class. So much for the old story about having your whole life flash before your eyes. The bicycle frame was bent, and the left pedal arm had been bent backward into the spokes. My left foot was just badly sprained. Shortly after that, I decided to leave town.

I was exhausted, depressed, and aimless. Busy as I was, I couldn’t keep up with all my classes. UMBC put me on academic probation, so I split. I had little money, just $100 I got back from someone I had loaned $200 to, so I got on my bicycle and rode. When I attempted to cross the Canadian border, I was searched. They found a bayonet knife I’d picked up for camping, and a few marijuana seeds. Then I was strip searched too. Nothing in my butt. Facing seven years of jail for smuggling a deadly weapon and “narcotics” across the border, I was simply denied entry. A young couple took me in for the night and fed me. I had pulled into a cul-de-sac at the end of a nearby street on the US side of the border. I was stymied – I didn’t know what to do or which way to go. I was full of frustrated energy, so I was riding my bicycle around in little circles, which caught their attention. They invited me in. They were watching the Watergate hearings on TV and making dinner. I regaled them with my border story and a bit of my life. I think we smoked some weed, because it got late, and they told me I could sleep on the couch. One thing they told me surprised me: they thought, at 22, that I was an old man! Between my long red beard, the long days of riding, and the snafu at the border, I was stressed out. They directed me to the best way to get to the next crossing. Before the Canadians had expelled me, a friendly border guard said he would delay sending the paperwork banning me from entering. Before I reached the next crossing, however, I stopped at a gas station to change clothes, and lost $50! I had split the $100 I had into two places – I would have removed my money from my jeans pocket when I changed into shorts, and must have left it sitting on the bathroom sink. I went back to see if it was there, and asked if it had been turned in, but no. So, I almost wasn’t allowed to cross the border, again, because having only $50 made it look like I was a bum who’d end up on welfare. I called an old roommate who had moved to Toronto and he vouched for me to the border guards.

Finally in Canada, I visited my former roommate in Toronto, to thank him. When I left Toronto I traveled northwest to visit a woman I’d known in an anti-war group at UMBC. She was working as a counselor for a kid’s camp. She had a boyfriend who glowered at me the whole time, so I didn’t stay long. A week of pedaling later, after being followed one night by a very large animal on a dark lonely highway, I met a beautiful old Canadian couple who offered me food and a nice outdoor sauna to clean up in. I likely smelled pretty bad. A day later, I visited Sault Ste. Marie during my stay at the hostel outside of that city. I stopped at a very nice park on the banks of St. Mary’s River, but I proceeded to get arrested for public drunkenness, courtesy of a couple local drunks who befriended me. After a night in jail, I was fined. Promising to get the money from the youth hostel I had been staying at, I packed up and left the country. I couldn’t afford to pay the fine and eat too.

Passing through several states back in the US of A, I joined a carnival as an electrician’s helper while crossing North Dakota. I spent the season traveling with them. One time, I deliberately brushed my finger against a 440-volt terminal in a junction box hooked to the giant-sized Big Bertha, one of the gas-powered generators I serviced. I was curious what would happen. I froze in shock for a few moments, almost frying my nervous system, but I survived. It reminded me of the time, barely 5 or 6 years old, when I decided to fix my parent’s alarm clock. I had watched my father fix electric wires by twisting them together and covering them with black electrical tape. Unfortunately, I twisted both wires together – blew the main house fuse. I think Death had been standing over my shoulder, again. One time I got my arm caught in the big steel cables that held the heavy steel panels enclosing two of the other four generators, also mounted on big rig trailers. The cable had almost crushed my arm, but it was only sprained, not broken. When the season ended, my plan had been to travel to Texas to visit Geri, the woman I had shared our first sex with in Baltimore. She had left town suddenly, not long after we met, and checked herself into a psychiatric hospital in Texas. I’d had other lovers afterward, before I left Baltimore, and, later in the carnival, but I wanted to see Geri, not only to find out why she had done that, but if we could reunite. It was not to be.

With the carnival season ending, the Murphy Brothers Exposition I’d joined was about to shut down for the winter in Tulsa, Oklahoma. They had already sent some of the big rides off to their home base while we finished up a small gig in Norman, Oklahoma. I met Cindy, a University student there, and with part of my season bonus money I’d rented a motel room – if you stayed the whole season you got a bonus. The “bonus” was actually money incrementally deducted from your pay every week. If you quit or got fired – no bonus. A common use of money as a carrot dangled in front of you to keep you going. I worked days at the small fair with what rides we still had, helping run the Tilt-a-Whirl. Old “Toothless” Lester ran that ride. Nights I spent with Cindy. It was glorious.

The day before the carnival was to move on, I checked out of the motel, saying goodbye to Cindy. We promised to stay in touch. I did visit her a couple years later, on my second bicycle trip west. She was staying in a motel in Oklahoma with a tennis player on tour. Nice guy. I was a bit disappointed, but Cindy asked him to leave us alone for a while, and he did. I was shocked, but the sex we had then was wonderful and sweet. I’d missed her. At one point she thanked me. I asked her, “What for?” She replied, “For all this,” waving her hand around the expensive suite. I assumed that included the tennis player, and a different lifestyle than she thought of before meeting me. She was enjoying her life. We stayed in touch, but at some point after that, she got married and had no more use for me. “I’m married,” she shouted in my ear when I got her on the phone.

But, after stashing my gear in the storage bay of the Tilt-a-Whirl I went back to work helping break everything down, which was how I’d hooked up with them in the first place. When I went back to the Tilt-a-Whirl, Lester was gone. So was my gear, and all of the money I had left. They went looking for him. He would often go on big drunks, they said, when he had money. He hadn’t gotten his season bonus yet, but finding mine, the booze called to him, and he disappeared. Now I was broke again, with only the clothes on my back (a sleeveless “muscle” shirt and jeans), and an old winter jacket Lester hadn’t taken. I asked the office if I could have the equivalent amount of money from his bonus that he had taken from me, but they just laughed. I was told I could continue working for a while, as some rides and joints would continue on to work small fairs. Bill, foreman of the Skydiver, one of the big rides, was going to Texas, and he needed people to set up and run that ride in Houston, and after that, Florida.

Houston offered new discoveries. Death was still watching me. I worked with two other guys on the Skydiver: Skeeter and Cherokee. Skeeter was an interesting tough guy. Well, carnies have to be to survive. He was heavily muscled and taciturn. Didn’t say much, except as it related to the work. Cherokee, thin and wiry, said he was indeed Cherokee, or partly, anyway. We got along. The Skydiver was about the size of a conventional Ferris Wheel but had cars enclosed with steel mesh. Once customers were in, we closed the mesh and locked it in place with a very large cotter key. A cotter pin is used to lock metal nuts in place on bolted items, threaded through a hole. The metal ends are twisted like twist-ties but with a pair of pliers. On the ‘Diver, the metal is shaped roughly like a lock key. It is a curved metal rod, bent in the middle and folded over. The top part is bent with ridges that help hold it in. It looks like a key but is made of steel, and not very flexible. We punched it in with the palm of our hands. To remove the “key” we would stick our middle finger in the opening that was created when the rod was bent, and yank hard. Our middle fingers developed strong muscles from doing that hundreds of frigging times a day.

So, one night, after we shut the ride down, and the townspeople had all left, we searched under the ride for coins. The cars people rode in could be spun using a small steering wheel, so not only were you going round and round, but spinning at a 90° angle to the ride’s rotation. People lost all kinds of things, like combs and pocket change. In fact, they lost so much, the three of us could buy dinner. One night, while walking back from a diner quite some distance away from the carnival, a car pulled up and offered us a ride. We were tired from the long work day, and sated with full bellies, so we jumped in. There were three guys in the one long front seat of those old wide-bodied Chevies. Once the car was moving, one of the guys pulled out a gun, a German luger, (PO4 9mm). They wanted our money and watches. None of us had a watch, and we had no money. We explained that we were carnies, and the guy pointing the luger at us smiled and lowered the gun. They were carnies too. Several carnivals would be set up sharing the same lot, as everyone had fewer rides on the road after the season-close. Then they offered each of us a watch. They had had a good day. I took one, a nice-looking Benrus. I wasn’t going to say no to a guy with a gun in his hand.

It wasn’t the only time I’d had a gun in my face. In the Skokie, IL. fairgrounds the cops had shown up one night after closing. A guy I knew who ran the Shoot-Out-The-Stars for a prize joint was riding his motorcycle around the race track alongside the fairgrounds. The cops had told him he couldn’t do that. He said, “OK,” and headed back to his trailer. However, the cops had meant, but hadn’t said, “Dismount Now!” So they were arresting him. It wasn’t long after closing, so a lot of us were still milling around. We slept under the rides or in trucks that hauled the rides and gear, but it was too early. Carnies protect their own, so everyone wandered over to see what was going on, including me. After all, that was a friend of mine. Well, the cops didn’t like that, so they ordered us to go home. This was our home, so we just stood there. I think they thought we were locals. Well, that freaked them out. Always afraid of the public they swear to protect, they pulled out their guns. The cop in front of me stuck his gun in my face. Damn, that was a big-bore gun! It must have been a 0.45. You don’t argue with a scared cop pointing a gun at you, because they get twitchy sometimes. The gun might go off, and you’re dead. If it’s investigated, they claim it was an accident, and they feared for their lives, so they were just doing what they were hired to do. Legal killing (murder) by the Blue gang.

I call them a gang because they play by gang rules, with a code of silence and closed ranks for anything a cop does. Sure, it’s a dangerous job, but maybe you shouldn’t be a cop if you’re that scared of the rest of the public. Driving is just as dangerous, and commercial fishermen die at a much higher rate than anyone else. So, I ducked behind one of the rides. The carnival protects their own too, so they bailed him out the next morning. No love between the carnies and the cops.

But, getting back to Houston, I will tell you how it went when we packed up the Sky Diver and headed to Florida. There were three semis loaded with gear: one with all the ‘diver cars, one with the hydraulically lowered ‘diver itself, and one with ponies. The foreman of the Sky Diver ride had bought himself a pony ride, one in which the ponies were hitched to a sort of large turnstile that they pushed around. It was a very popular ride with the tiny tots. Bill, the foreman, also had a station wagon that he used to pull the pieces of the brightly colored orange and yellow turnstile in a small trailer. Bill, Skeeter, and Cherokee each drove a truck. I knew how to drive and back up a big rig. But, I wasn’t licensed for that, so I got to drive Bill’s station wagon. I got lost on Houston’s big highway interchange and missed the turn for Interstate 10. By the time I went round and round to make my way east, I sped up to try and catch up to the others. I never did. Just outside of Jennings, Louisiana, a trailer wheel snapped off. The trailer body hit the road on that side. The effect was to spin me around. It also turned the trailer upside down in the process. I’d been doing 70 mph. I saw the pieces of the turnstile in the air all around me. The yellow and orange pieces floating in the air reminded me of fire. When everything stopped, I was facing the wrong way, towards traffic, blocking both eastbound lanes of I-10. I was arrested, again, this time for “Failure to maintain control of my vehicle,” a fineable offense. Since I didn’t have any money, I couldn’t pay the fine.

Long story short, the Carnival got me out the next day, after I’d spent a sleepless night reading a book I’d found in my solitary cell (autobiography of Joan Baez). Since I was in a corner cell, I talked with my neighboring cells. The guy to my left asked if I had any dope. I told him I did, just a few ounces of weed in a baggie I’d managed to smuggle in. While being searched, I had my hands hooked in my front pockets since the one-armed deputy booking me searched my back pockets first, one at a time. Then he told me to raise my arms. That had given me time to slip the baggie inside my fist, so I raised it high while he searched the front pockets, and then I slipped it into my back pocket when he told me to lower my arms. I had money wired to me from the carnival to fix the car. The cops had gathered every bit of that pony ride and put it back into the trailer. I spent the next night sleeping in the break room used by the trustees. I was told to take whatever I wanted from the refrigerator. Nice. On the way to Florida, however, the car broke down on that long section of bridge across Louisiana swamp. A radiator hose had been cracked in the accident. I spent hours letting the engine cool, then driving until the temperature gauge was pinned on high again, over and over, and over, and over. There was about three or four feet of space between the road and the guardrail, so the rigs swooshed by me the whole time, barely missing me.

One hell of a lot of loud truck horns blared at me, but what could I do? There is no exit on the Atchafalaya Basin Bridge for 18 miles. There’s only water left and right. Again, I survived. After a disappointing stay in Florida, in which, while Bill went back for his car and trailer, we set up the Sky Diver by ourselves. Scary thing that. It’s huge and full of heavy steel beams. As we raised the ride in sand, it almost tipped over, scaring the wits out of us. We hadn’t spread enough wood under the legs to stabilize them, so we got it right. But there was no money to be made there, so I finally headed on up the coast to visit a trio of young ladies I’d met in Canada. I spent one bitter cold mountain night outside in an empty car on a gas station lot while I waited to transfer to the morning bus. The ride foreman had given me busfare, and driven me to the station to make sure I got on. When the bus stopped to let me off, I was still mostly asleep. The bicycle was still on the bus, which had raced off as soon as I had stepped down. I spent the winter night awake, shivering violently in an old car at a gas station. In the morning the bus returned, with my bicycle. The girls were sure surprised to see me, and I stayed on a bit, chopping firewood and helping out. I finally overstayed my welcome but was being offered a job raising goats on a neighboring farm. I declined. I decided to take a train back to Baltimore, where I’d started. It was supposed to have been a round trip after all.

But, I had hours to kill while I waited for the train. “Desperado waiting for a train….” Really, I was no desperado, but I waited in a pool hall, shooting pool with an old codger who played like a shark. Bang, bang, bang went the shiny numbered balls into the pockets. I had nothing but pocket change, so we played for the table. I paid for several games. I finally got a chance to shoot. I lined up the cue ball and steadied my cue stick on it when bang, bang, bang – gunshots outside. Shocked, I looked up. Everyone in the place was running out the door. Damn, those cats were fast. I was the last one out. I walked out right next to the shooter. One man was down and out on the ground. The shooter didn’t notice me at first because he was busy pumping some more lead into the guy on the ground. The body jerked with each shot. Either the shooter was out of bullets, or he suddenly noticed me. He turned to me. I looked him in the eyes, not in a show of force or strength, but because I didn’t know what else to do. He must have thought I wanted to know why he was doing that, which I was. He said to me, “He deserved it.” Now I’d given that idea some thought in the past, and I don’t think it’s anyone’s job to decide who dies unless they are able to control who doesn’t have to die. The words scrolled across my brain, but I couldn’t get them to my mouth. He stared at me for I-don’t-know-how long. It was probably seconds, but it felt like time had stopped. Finally, he lowered the gun, did an about-face on one heel, and slowly walked off.

By this time, an ambulance was arriving, along with some cops in patrol cars behind it. I waited around. A gurney was produced from the ambulance. A blanket was placed over the quite young guy on the ground, but not covering his face, so maybe he was still alive? They loaded the gurney back into the ambulance, and they sped off, sirens wailing. I had been waiting for the cops to come over and ask for statements from witnesses, especially me, since I had been inadvertently eyewitness to some of it, but they got in their cars and drove away, following the ambulance. After some moment in time, I decided to return to the pool hall. Somehow, most of the pool players were already back. I asked my pool partner from the time before time had stopped if he wanted to continue. He said yes, so I went back to my shot, lined the balls up quickly, and shot. The cue ball flew off the table and rolled crazily away at high speed. My pool partner retrieved it. When he came back, he said, “Maybe we should call it a night.” I had to agree with him. I think my nerves were shot. The train ride to Baltimore was sobering. My thoughts were full of gunshots and daydreams. I didn’t know what to expect in Baltimore, but I wanted to rest.

I found a job fairly quickly. I sent money to the Sky-Diver foreman Bill, feeling like I owed him. He wrote back in a shaky hand, thanking me for that, using simple printed words. I used to write letters all the time while I was working on the carnival, so I had to assume Bill never had the schooling I had. A good man. I looked up Judy White, whom I’d been writing to, someone I’d briefly dated before, but there was no chemistry between us. I don’t think there ever had been. I dated some after that, but nothing clicked. I was never good at relationships, just enjoyed the comfort of sex and sharing a bed. When my job suddenly ended, there was no longer any reason to stay in the town of my birth. I gave away what possessions I’d accumulated, loaded my bicycle up with clothes, food, and tools, and headed westerly.

I stopped in Arizona, working for a bronze foundry for about nine or ten months, before heading out on another bicycle trip across the USA, but this time with a group of bicyclists heading slowly eastward towards Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. On the way, we stopped in many cities and towns, including Albuquerque, New Mexico, where I somehow stole the heart of a married woman. Her husband split, but I wasn’t finished with my travels yet. She divorced after I left and wrote to me often. I hadn’t found a good job in Pittsburg, so I went to New York City with my bicycle. I became a bicycle messenger. I had some friends there. They had an organization and a newspaper called, “Don’t Mourn, Organize,” a phrase used by the famous union organizer Joe Hill. Their mission was to organize tenant councils for the working poor and people on welfare, as had been done during the “Great Depression” in the 1930s. One of them let me stay at his apartment since he was rarely home. Riding a bicycle all day in the bitterly cold streets of NYC in winter is no fun, and dangerous. Drivers are insane there. The woman I’d met in Albuquerque wanted me to come live with her. I did. After a year and a half, that relationship suddenly ended one day, but I stayed. I like it here in Albuquerque.

In a flash forward, I am riding a motorcycle near my home in my newly adopted home state of New Mexico, when a Bernalillo County sheriff pulls me over, I don’t remember why. Sometimes they don’t provide a reason. He asked for my “registration and proof of insurance,” of course. I had a hinged seat, so I unlocked and popped it open because that’s where I kept them back then. As I reached for them, he went for his gun. I explained, but he kept his hand on the gun butt – the holster, unsnapped. Cops were quite leery of motorcyclists back then, but he didn’t shoot me. He allowed me to continue. I either have a devil on my ass or a guardian angel.

Speaking of which, I went sailing over a car that pulled in front of me twice, once on my bicycle, and once on my motorcycle. Bad sprain the first time, just bruised and sore the next time. Bicycle and motorcycle totaled. Once I missed the light change with the sun in my eyes at an intersection and plowed into a pickup. Motorcycle totaled. I’d been going about 40 to 45 mph and didn’t have time to brake. Just bruised, sore as hell, and had to wear my arm in a sling for a bit. The driver said I bent the frame of his truck. I didn’t buy that, and neither did my insurance company.

One night, a car ran into me while I was crossing a street on foot. I was three-quarters of the way across and under a streetlight, but she had raced around the corner, going south, steering wide into the northbound lane where I was. She pushed me down the street while I was still on my feet. I didn’t fall down until she suddenly braked hard. Now that threw me down hard, painfully. I was not badly hurt, but one edge of my left shoe was ground down and ruined. I didn’t visit the emergency room or call the cops. I was OK. No damage, just bruised and sore again. I figured out later, from things she said, that she had run out of the art show we’d both been at, looking to stop me. I had bought two small lithograph prints while I’d been there. I’d gone because it was opening night, and there is usually free food and drink at such things. The woman was one of the artists. I’d stopped to browse a small rack of prints by the exit before I left. Realizing how late and cold it was, I stopped browsing and hurried out. I had a short walk half a block away to the side road I’d parked my car on. As I stepped into the street, I noticed a car’s headlights to my left. It was turning into the street I was in, so I rushed into the far lane to get out of the way. She hit me softly, but then she sped up. I could feel the acceleration until she braked. When I got up, she was out of her car, asking if I was OK. I felt OK, and walked over to where I dropped the bag with the small prints. She said, “Oh! you bought something there.” That puzzled me, from the way she said it – something in her voice.

Years later, I read that the local technical vocational college was looking for stories about pedestrian-car accidents. I let them interview me and asked if they wanted to speak with the woman who had hit me. Since they did, I called her. In a high-pitched, shaky voice, she said, “No. I never want to think about that night again.” I explained that I was OK with what had happened, but she was adamantly opposed to meeting with the college people, or ever speaking of that “incident”, as she called it. Then I figured out that she had been after me, angry, hoping to recover whatever she thought I stole, and single-mindedly drove right into me. Having a car pushing me down the street was a surreal experience. The acceleration kept me pinned to the car’s bumper at a slight angle. If only she hadn’t panicked and slammed on the brakes, I wouldn’t have been in so much pain later. Adrenaline temporarily suppressed the pain of that. I had hit my right hip and shoulder hard on the asphalt. Hitting my shoulder aggravated an old motorcycle accident when I’d gone off the road on a sharp curve years before. That still bothers me some days.

I’ve lost two cars to bad drivers too. In Placitas, NM, a driver turned a corner and rammed me head-first. I was braked, about to turn right, west, and had turned my head to look for traffic to my left. I was as far to the right as I could possibly be, with no cars in sight when I stopped. She had been heading east in the far lane, and again, instead of turning into the far lane on the two-way street I was on, she turned into my lane. She blamed me – said I was too far forward. Although the front end of my car was about three feet past the stop sign, there was at least six feet between me and the highway. My brain was sore for weeks – it must have rattled around in my skull. My insurance company spoke with her, and she confirmed that the accident had occurred on the side street I was on. Since it was a front-end collision, there was no way I could have run into her, or I’d have damaged the side of her car. My insurance sided with me, but her insurance claimed it was my fault.

It happened again, of course. I pulled into a center turn bay on Albuquerque’s 4th Street, waiting for southbound traffic to stop, so I could get groceries. It took a while for traffic to clear. I had seen a pickup waiting to come out. When traffic cleared I began my turn, but just then he raced out. I completed my turn and sped up to get out of his way, but he hit me along the driver’s side, still accelerating – I could feel my car being pushed. The whole side was creased badly, and the rear door was crushed shut. Old guy, very old, and a sturdy pickup. He said it was his fault, and that he hadn’t seen me. The accident had occurred in the the southbound lane, and he had been turning north before he reached the opposite lanes, so, clearly his fault. If he had not turned until reaching the center, he wouldn’t have hit me. Later, while waiting for the cops, he stared at my car, then said, referring to my car’s color, “That’s what happened. I couldn’t see that light green.” I thought, “And you’re allowed to drive why?”

Hell, the same thing had happened back when I had first moved to Albuquerque. I was driving my new girlfriend’s car home from a union meeting too far away to have ridden my bicycle, my only ride. A seventeen-year-old with a learner’s permit had followed another vehicle into the intersection without stopping at the stop sign. That first vehicle was stopped in the middle of four-lane Central Avenue, waiting to join eastbound traffic, so the seventeen-year-old had no place to go. I steered that car hard right, but I was too close and hit the other car’s left fender. Same kind of thing. The boy’s mother was with him, and she claimed I was going too fast. The tire tracks I made when I braked proved that I was under the speed limit, not that it mattered. We went to court, but before we got called into the courtroom, they decided to settle. They agreed to pay for the front-end damage to my girlfriend’s car over time. It never got fixed. It just sat for a long time. I don’t know if she ever got the money because she left me for someone else not too long after that. The car actually belonged to her ex-husband, who had moved to France after she’d taken up with me. But, that’s part of another story. He was still angry, and he wanted that car back.

It took a lot to get anything done. Of course that experience helped me get a job in a research lab just before I graduated from high school.

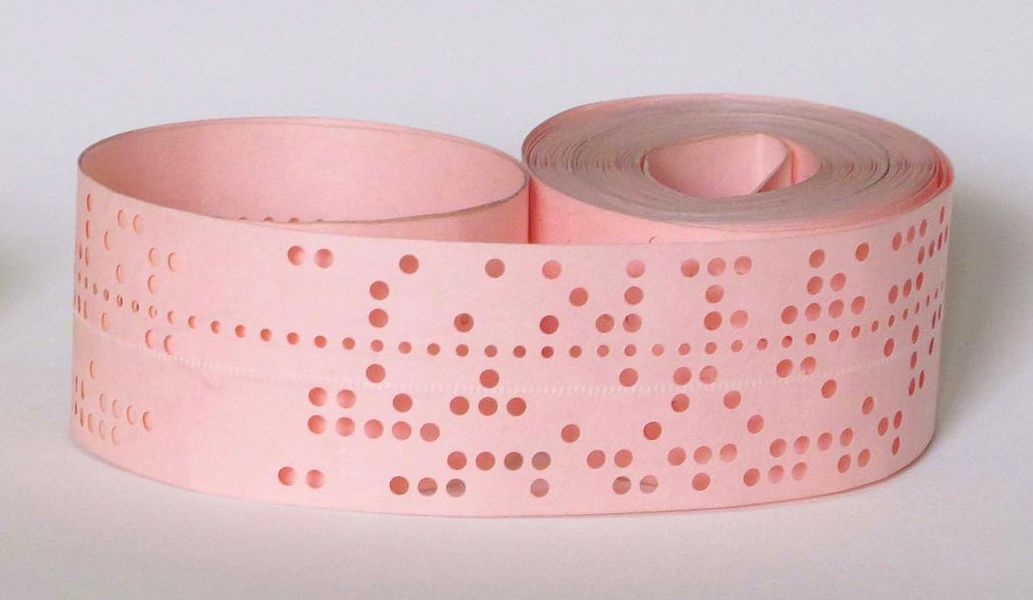

It took a lot to get anything done. Of course that experience helped me get a job in a research lab just before I graduated from high school. At the end of every day, I walked the tape to the “computing center” and loaded the tape on a reel in a device that converted the punched holes in the tape to punch cards. There was a program already punched into a set of cards, and held together with a rubber band, so I banded that together with the cards from the data I’d collected, and then handed it to the folks at the counter. One did not get near the computers. The techs stacked the cards to run overnight with all the other jobs. I picked up the results the next day as a printout. It was all just a series of average measurements, with statistical info out to seven decimal places. The whole computing center building was greatly refrigerated due to the heat generated by the computers — in the same way computer chips need a cooling fan. Very expensive and energy consuming. And the computer people had to wear coats. Mind you, this was state-of-the-art computing at Johns Hopkins University at the time (late 60s & early 70s).

At the end of every day, I walked the tape to the “computing center” and loaded the tape on a reel in a device that converted the punched holes in the tape to punch cards. There was a program already punched into a set of cards, and held together with a rubber band, so I banded that together with the cards from the data I’d collected, and then handed it to the folks at the counter. One did not get near the computers. The techs stacked the cards to run overnight with all the other jobs. I picked up the results the next day as a printout. It was all just a series of average measurements, with statistical info out to seven decimal places. The whole computing center building was greatly refrigerated due to the heat generated by the computers — in the same way computer chips need a cooling fan. Very expensive and energy consuming. And the computer people had to wear coats. Mind you, this was state-of-the-art computing at Johns Hopkins University at the time (late 60s & early 70s).  the interface was a small keypad with tiny buttons — really tiny screen, really tiny buttons. My boss also had a stand-alone HP-85, run off of a program cartridge that controlled research equipment for column chromatography, and it had a nicer keyboard.

the interface was a small keypad with tiny buttons — really tiny screen, really tiny buttons. My boss also had a stand-alone HP-85, run off of a program cartridge that controlled research equipment for column chromatography, and it had a nicer keyboard.  We upgraded that one with an external floppy disk, for storage, just one disk at first, and then with two drives for copying disk to disk — woo hoo! On this machine, I had a simple line-drawing ski game to play. Then – OMG – my boss got a desktop computer in 1985. A 10Mb hard drive! A full-sized keyboard interface. but all commands had to be typed in with DOS commands, using a blank screen.

We upgraded that one with an external floppy disk, for storage, just one disk at first, and then with two drives for copying disk to disk — woo hoo! On this machine, I had a simple line-drawing ski game to play. Then – OMG – my boss got a desktop computer in 1985. A 10Mb hard drive! A full-sized keyboard interface. but all commands had to be typed in with DOS commands, using a blank screen.

Then the drop-down program menus needed a mouse, or awkward combinations of multiple keys to select commands, so I got a mouse. Progress.

Then the drop-down program menus needed a mouse, or awkward combinations of multiple keys to select commands, so I got a mouse. Progress.

in the 1970s, and Commodore VIC-20s and Atari 400 home computers on the market in the early 1980s, but those cost two or three months’ rent. The Atari 800

in the 1970s, and Commodore VIC-20s and Atari 400 home computers on the market in the early 1980s, but those cost two or three months’ rent. The Atari 800  cost about $1000, six months of rent or more. The cost of MACs was insane. By 1988, I was able to purchase a used DOS personal computer (Disk Operating System, aka desktop) for myself at home, using student loan money. Mostly I needed it to write papers, because, without it, I had to type. In my classes where I had been typing 25-page papers, I was graded on spelling and punctuation in addition to the subject matter. I went through a lot of typing paper and time trying to get my papers perfect.

cost about $1000, six months of rent or more. The cost of MACs was insane. By 1988, I was able to purchase a used DOS personal computer (Disk Operating System, aka desktop) for myself at home, using student loan money. Mostly I needed it to write papers, because, without it, I had to type. In my classes where I had been typing 25-page papers, I was graded on spelling and punctuation in addition to the subject matter. I went through a lot of typing paper and time trying to get my papers perfect.

on this cross-country bicycle trip, Nancy, saw this trip’s purpose primarily as networking. She wanted to help connect with all sorts of active people around the country, trading information and distributing contact information. So any chance she had she was talking to people, interviewing them, picking up more books and literature. Peaceful change was her goal, and not far from what I had worked for myself. Beside my participation in antiwar marches, lobbying, and organizing, I had spent years volunteering with a free medical clinic in Baltimore, Maryland, the city of my birth. The Clinic had been started by anti-war activists, a local chapter of the Black Panthers, and free-school teachers, among others, including some doctors.

on this cross-country bicycle trip, Nancy, saw this trip’s purpose primarily as networking. She wanted to help connect with all sorts of active people around the country, trading information and distributing contact information. So any chance she had she was talking to people, interviewing them, picking up more books and literature. Peaceful change was her goal, and not far from what I had worked for myself. Beside my participation in antiwar marches, lobbying, and organizing, I had spent years volunteering with a free medical clinic in Baltimore, Maryland, the city of my birth. The Clinic had been started by anti-war activists, a local chapter of the Black Panthers, and free-school teachers, among others, including some doctors. New Buffalo, one of the largest and well-known communes, was an interesting place. Farming, and self sufficiency were the norm there. There was music, and basic, plain food. We actually found ourselves criticized for not living a lifestyle like theirs. We had two writers with us, Nancy, and also Rick from San Francisco, which is where the bike group had left from. The folks at New Buffalo felt they were committed to a lifestyle that would change the world, whereas we were just tourists, getting paid to write. I thought that was a bit unfair, and personally, I felt that the people at New Buffalo were just dropouts, too far removed from society to change it. In the Easy Rider film, Peter Fonda’s character had said he thought they could make it. Dennis Hopper’s character didn’t think so. Hopper himself hung out in Taos. New Buffalo’s lifestyle was very laid back, but people had been leaving it for some time. The remainder were a bit fanatic. I wanted to see our culture change too, to see us go from a country that always seemed to be fighting somewhere around the globe, threatening to destroy the entire planet with our nuclear weapons, and polluting not only rivers and streams, but oceans and the very air we breathed. You couldn’t escape that by living out of the way and off the grid. Nice for them, but wouldn’t change a thing. It was strange to argue with people whom I’d thought were much like me, but they were too fanatical to think there was any other way but theirs. Although the commune had been founded 9 years earlier, we had to use corn cobs to wipe our butts in the outhouse. They weren’t just trying to reduce paper waste; they wanted to use the outhouse sludge on their crops. I was trying to survive too, but looking for actual ways to restructure society to benefit all. I had a more political bent, from my anti-war activities, and my experiences helping to provide community health care with the goal of universal health care. I didn’t enjoy my time at New Buffalo, so I was happy to get on up the road the next day.

New Buffalo, one of the largest and well-known communes, was an interesting place. Farming, and self sufficiency were the norm there. There was music, and basic, plain food. We actually found ourselves criticized for not living a lifestyle like theirs. We had two writers with us, Nancy, and also Rick from San Francisco, which is where the bike group had left from. The folks at New Buffalo felt they were committed to a lifestyle that would change the world, whereas we were just tourists, getting paid to write. I thought that was a bit unfair, and personally, I felt that the people at New Buffalo were just dropouts, too far removed from society to change it. In the Easy Rider film, Peter Fonda’s character had said he thought they could make it. Dennis Hopper’s character didn’t think so. Hopper himself hung out in Taos. New Buffalo’s lifestyle was very laid back, but people had been leaving it for some time. The remainder were a bit fanatic. I wanted to see our culture change too, to see us go from a country that always seemed to be fighting somewhere around the globe, threatening to destroy the entire planet with our nuclear weapons, and polluting not only rivers and streams, but oceans and the very air we breathed. You couldn’t escape that by living out of the way and off the grid. Nice for them, but wouldn’t change a thing. It was strange to argue with people whom I’d thought were much like me, but they were too fanatical to think there was any other way but theirs. Although the commune had been founded 9 years earlier, we had to use corn cobs to wipe our butts in the outhouse. They weren’t just trying to reduce paper waste; they wanted to use the outhouse sludge on their crops. I was trying to survive too, but looking for actual ways to restructure society to benefit all. I had a more political bent, from my anti-war activities, and my experiences helping to provide community health care with the goal of universal health care. I didn’t enjoy my time at New Buffalo, so I was happy to get on up the road the next day. It was one of the most well known communes in the area at the time, and one of the few left now. New Buffalo is now a B&B. This was the first time I’d ever seen an outhouse designed for two people to use at the same time, but that wasn’t the oddest thing. The shit holes had been designed low to the ground with painted shoe prints on either side of the holes. Apparently it is considered better for people to shit crouched down like that. At the time, I had no idea this was common in other countries. I liked this place much better than New Buffalo. The people seemed almost beatifically happy. They had small cottage industries going, and reached out to people in Taos, Santa Fe, and native communities as well. Such a difference from the grungy drop-outs at New Buffalo! There was a lot to see around the Lama commune, and we were welcome guests. Nancy was in heaven, interviewing people. People there were not critical of others, and did their best to demonstrate a better way of life. The food was much better there too, but I didn’t stay long. A green MG drove up. It was Isla, from Albuquerque. She’d come to see me, but really she wanted me to go back to Albuquerque with her. She asked me to just come back for two weeks, so we could get to know each other. I agreed. I told Darla I was leaving for a couple weeks. She didn’t seem entirely happy about that, but we barely knew each other either. On the drive back to Albuquerque, with my bicycle strapped across the back of the little car, Isla told me she and Carl had never wanted to have children, or rather that she hadn’t wanted to have children. I think Carl was the type to want children. He really was a nice guy. Guilt. Guilt.

It was one of the most well known communes in the area at the time, and one of the few left now. New Buffalo is now a B&B. This was the first time I’d ever seen an outhouse designed for two people to use at the same time, but that wasn’t the oddest thing. The shit holes had been designed low to the ground with painted shoe prints on either side of the holes. Apparently it is considered better for people to shit crouched down like that. At the time, I had no idea this was common in other countries. I liked this place much better than New Buffalo. The people seemed almost beatifically happy. They had small cottage industries going, and reached out to people in Taos, Santa Fe, and native communities as well. Such a difference from the grungy drop-outs at New Buffalo! There was a lot to see around the Lama commune, and we were welcome guests. Nancy was in heaven, interviewing people. People there were not critical of others, and did their best to demonstrate a better way of life. The food was much better there too, but I didn’t stay long. A green MG drove up. It was Isla, from Albuquerque. She’d come to see me, but really she wanted me to go back to Albuquerque with her. She asked me to just come back for two weeks, so we could get to know each other. I agreed. I told Darla I was leaving for a couple weeks. She didn’t seem entirely happy about that, but we barely knew each other either. On the drive back to Albuquerque, with my bicycle strapped across the back of the little car, Isla told me she and Carl had never wanted to have children, or rather that she hadn’t wanted to have children. I think Carl was the type to want children. He really was a nice guy. Guilt. Guilt.

or working as a carnival electrician, hooking up all the rides, joints and food stands. I was on the road a lot, bicycling my way back and forth across the United States when I met her.

or working as a carnival electrician, hooking up all the rides, joints and food stands. I was on the road a lot, bicycling my way back and forth across the United States when I met her. a former journalist, Peace Corps volunteer, and currently director of a public advocacy group, who had offered her home to any of us that needed a space to crash while we visited her city. I don’t know if she’d cleared that with her husband before making that offer. He was a nice guy, a jewelry maker, but she was her own woman. There had been a list of these prearranged homestays (crash houses, I called ‘em), and I picked her place, not yet knowing whose place it was. I had dialed a number. A woman’s voice had answered. She had seemed quite happy that someone had called, and told me to come by that evening. The bicycle group had a sag wagon, an old school bus, powered by propane, and painted white.

a former journalist, Peace Corps volunteer, and currently director of a public advocacy group, who had offered her home to any of us that needed a space to crash while we visited her city. I don’t know if she’d cleared that with her husband before making that offer. He was a nice guy, a jewelry maker, but she was her own woman. There had been a list of these prearranged homestays (crash houses, I called ‘em), and I picked her place, not yet knowing whose place it was. I had dialed a number. A woman’s voice had answered. She had seemed quite happy that someone had called, and told me to come by that evening. The bicycle group had a sag wagon, an old school bus, powered by propane, and painted white.  It sported a library, a folded-down wind generator, and a cook stove, but it had no bathroom or shower, and oh boy! did I need a shower. When I arrived, dinner was ready. This friendly couple welcomed me into their very small home near the zoo. I had been expecting an elderly couple, because in my experience staying in the homes of church people, years earlier, who had supported us anti-war protesters when we were far from home, they’d always been wrinkly old couples.

It sported a library, a folded-down wind generator, and a cook stove, but it had no bathroom or shower, and oh boy! did I need a shower. When I arrived, dinner was ready. This friendly couple welcomed me into their very small home near the zoo. I had been expecting an elderly couple, because in my experience staying in the homes of church people, years earlier, who had supported us anti-war protesters when we were far from home, they’d always been wrinkly old couples. Isla was a real joy, full of delightful conversation and a fountain of information about the city. She drove north through a valley full of large rich homes with huge lawns, surrounded by imposing trees – cottonwoods – which I had never seen before. I was so surprised to see such greenery in an area I’d thought of as a desert. This city seemed like an oasis. We stopped by Carl’s workplace, as there was a great local restaurant nearby where we could all have lunch together. Carl was pretty busy, and didn’t have time to join us. And it turned out the restaurant was in the middle of renovations anyway, so we drove off.

Isla was a real joy, full of delightful conversation and a fountain of information about the city. She drove north through a valley full of large rich homes with huge lawns, surrounded by imposing trees – cottonwoods – which I had never seen before. I was so surprised to see such greenery in an area I’d thought of as a desert. This city seemed like an oasis. We stopped by Carl’s workplace, as there was a great local restaurant nearby where we could all have lunch together. Carl was pretty busy, and didn’t have time to join us. And it turned out the restaurant was in the middle of renovations anyway, so we drove off.

It is far stranger than Mussorgsky ever imagined, of that I am sure. I like some of Tomita’s works very much. This one not so much. Lately I have acquired many CDs of his work. I love his live concert, done in 1984: The Mind Of The Universe,

It is far stranger than Mussorgsky ever imagined, of that I am sure. I like some of Tomita’s works very much. This one not so much. Lately I have acquired many CDs of his work. I love his live concert, done in 1984: The Mind Of The Universe,  and have enjoyed his version of

and have enjoyed his version of  Debussy’s tone paintings. However, I disliked his version of

Debussy’s tone paintings. However, I disliked his version of  “It is the story of TJ, a young man from a privileged family, who drops out of law school against his mother’s wishes to pursue his dream of becoming an MMA fighter.” I was fascinated by it, and the gym, as this was the first time I’d ever been in one.

“It is the story of TJ, a young man from a privileged family, who drops out of law school against his mother’s wishes to pursue his dream of becoming an MMA fighter.” I was fascinated by it, and the gym, as this was the first time I’d ever been in one. I’ve really enjoyed the first half, but could not get back into it today; perhaps I will later this evening. Hosseini wrote

I’ve really enjoyed the first half, but could not get back into it today; perhaps I will later this evening. Hosseini wrote  , I did not read the book. Hosseini is a good writer, and writes real stories of real people caught up in circumstances of violence and social change beyond their control, sometimes beyond all comprehension.

, I did not read the book. Hosseini is a good writer, and writes real stories of real people caught up in circumstances of violence and social change beyond their control, sometimes beyond all comprehension. Hopefully it is not, but it is a good introduction to Tomita’s work. Some are very good, some are fascinating, and some are just odd, which is pretty much how I feel today.

Hopefully it is not, but it is a good introduction to Tomita’s work. Some are very good, some are fascinating, and some are just odd, which is pretty much how I feel today. He and my mom roller skated a lot growing up, and were partnered by their coach for competitions, which they won a lot of, being Tri-State champions at it. I’m told they did not like each other at first,

He and my mom roller skated a lot growing up, and were partnered by their coach for competitions, which they won a lot of, being Tri-State champions at it. I’m told they did not like each other at first,  but they appear to have gotten over that. My dad died of lung cancer many years ago. I wish he was around. I’d love to pick his brain. Oddly, when I posted that photo of him, all my mom could think of to comment on was the fact that his skates had wooden wheels, as they all did back then. When she commented, I noticed that she had changed her profile picture to a photo of her in 1978. I was living in Albuquerque at the time, and had no money for plane tickets, so I never knew she had changed her hairstyle so dramatically –

but they appear to have gotten over that. My dad died of lung cancer many years ago. I wish he was around. I’d love to pick his brain. Oddly, when I posted that photo of him, all my mom could think of to comment on was the fact that his skates had wooden wheels, as they all did back then. When she commented, I noticed that she had changed her profile picture to a photo of her in 1978. I was living in Albuquerque at the time, and had no money for plane tickets, so I never knew she had changed her hairstyle so dramatically –  – 1970s big hair. My brother said it’s her Liz Taylor look. I swear I’d never have recognized her on the street in that hairdo. She and my father were divorced by then, and I probably didn’t see her for many years after I left town permanently in 1975. She must have added the flag banner via Facebook, perhaps for Memorial Day. She’s 87 years old now.

– 1970s big hair. My brother said it’s her Liz Taylor look. I swear I’d never have recognized her on the street in that hairdo. She and my father were divorced by then, and I probably didn’t see her for many years after I left town permanently in 1975. She must have added the flag banner via Facebook, perhaps for Memorial Day. She’s 87 years old now.

After all the lights and seats were off, hydraulics lowered the ride slowly down into the trailer, while Sean and a few others lifted the braces out and away from the ride. After the ride was safely lowered into its trailer, they lifted each heavy brace and tucked it into the other trailer, the one that would carry the individual seats as well. When that was done, the foreman told Sean to ask the office what else he could do. When Sean told the man in the office window the wheel was finished, he looked surprised. “Look over there. See that big generator with the light tower on it? Ask for Duane. He’s the electrician. He needs help.” Sean trotted off and found Duane. Duane was a short, muscular young man, with short blond hair and a bushy mustache.

After all the lights and seats were off, hydraulics lowered the ride slowly down into the trailer, while Sean and a few others lifted the braces out and away from the ride. After the ride was safely lowered into its trailer, they lifted each heavy brace and tucked it into the other trailer, the one that would carry the individual seats as well. When that was done, the foreman told Sean to ask the office what else he could do. When Sean told the man in the office window the wheel was finished, he looked surprised. “Look over there. See that big generator with the light tower on it? Ask for Duane. He’s the electrician. He needs help.” Sean trotted off and found Duane. Duane was a short, muscular young man, with short blond hair and a bushy mustache. With a nearly blinding flash of giant sparks, the wire welded itself to the hole, and simultaneously the lights went out as Big Bertha, the giant generator, popped its main breaker. Rides still being turned or lowered shut off. There was a sudden dark silence. Sean heard curses. Duane ran over. Sean said, “Touched the side. Sorry.” Duane yanked the wire hard, away from the box and ran for the generator. He threw the breaker and that section of midway lit up again, noise blaring from rides and cheers from the workers stuck in the near dark. “Just be careful OK?” “Sure,” Sean said, relieved. He thought he’d screwed up badly already. Just after the lights had come back on he’d heard someone yell, “Hey, we got a new electrician.” He took each wire off slowly after that. He was no longer in a hurry. Later Duane had him pull the wires, bundles of three one inch copper wires, and a 3/8″ ground wire, into a trailer and coil each one, layering the coils in the truck. Sean could barely lift the hundred-foot-long bundles at first. Usually he pulled the wires over to the truck and threw one end in. From inside he could pull the wires into a neat coil. He spent the night doing that: disconnecting, pulling, coiling, back and forth all over the midway. At the end, the generators, for there were more than one, had to be turned off, and the trailers closed up in preparation for the long drive. Duane paid Sean for the work. Sean turned to go, happy to have picked up some money, but Duane stopped him. “Say, you want to work for us?” “But I shorted out the generator.” “No biggie. You’re alive, ain’t ya?” “Well, yeah.” “Well, you want a job or not?” “Yeah, sure.”

With a nearly blinding flash of giant sparks, the wire welded itself to the hole, and simultaneously the lights went out as Big Bertha, the giant generator, popped its main breaker. Rides still being turned or lowered shut off. There was a sudden dark silence. Sean heard curses. Duane ran over. Sean said, “Touched the side. Sorry.” Duane yanked the wire hard, away from the box and ran for the generator. He threw the breaker and that section of midway lit up again, noise blaring from rides and cheers from the workers stuck in the near dark. “Just be careful OK?” “Sure,” Sean said, relieved. He thought he’d screwed up badly already. Just after the lights had come back on he’d heard someone yell, “Hey, we got a new electrician.” He took each wire off slowly after that. He was no longer in a hurry. Later Duane had him pull the wires, bundles of three one inch copper wires, and a 3/8″ ground wire, into a trailer and coil each one, layering the coils in the truck. Sean could barely lift the hundred-foot-long bundles at first. Usually he pulled the wires over to the truck and threw one end in. From inside he could pull the wires into a neat coil. He spent the night doing that: disconnecting, pulling, coiling, back and forth all over the midway. At the end, the generators, for there were more than one, had to be turned off, and the trailers closed up in preparation for the long drive. Duane paid Sean for the work. Sean turned to go, happy to have picked up some money, but Duane stopped him. “Say, you want to work for us?” “But I shorted out the generator.” “No biggie. You’re alive, ain’t ya?” “Well, yeah.” “Well, you want a job or not?” “Yeah, sure.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.